Early this month I spent some time in Vanuatu, and some of it was on the island of Santo, including Palikulo Bay which you’ve probably no reason to have heard of. I’ve marked it on the map, assuming you can find Vanuatu at all (Google is your friend). What you need to know is that it is a tiny country in the Pacific, about the same latitude as northern Australia but about 2000km to the east, so there is a lot of ocean around it. Apart from the whole tropical island paradise thing they have going on (and they really do have that going on) these islands were important during WWII. There is debris left over from the military operations, not everywhere, but where you find it you find lots of it.

Santos was a forward base put together by the US forces to block the Japanese advance through the Solomon Islands. It was an enormous undertaking done at breakneck speed. They had to have a working air base established before the Japanese could occupy Guadalcanal 500km to the north west. They had mere weeks to get this done on an island with practically no infrastructure that was a very long way from anywhere.

At the time the local population must have been under 10,000. They had had contact with the outside world, there were trade routes to the nearby island groups that pre-date European discovery. Many of them had gone to work in Australia a couple of generations before (some of that was not voluntary), and they’d had missionaries living among them for decades. But you should imagine a low tech subsistence lifestyle. Most of them would not have seen an aircraft.

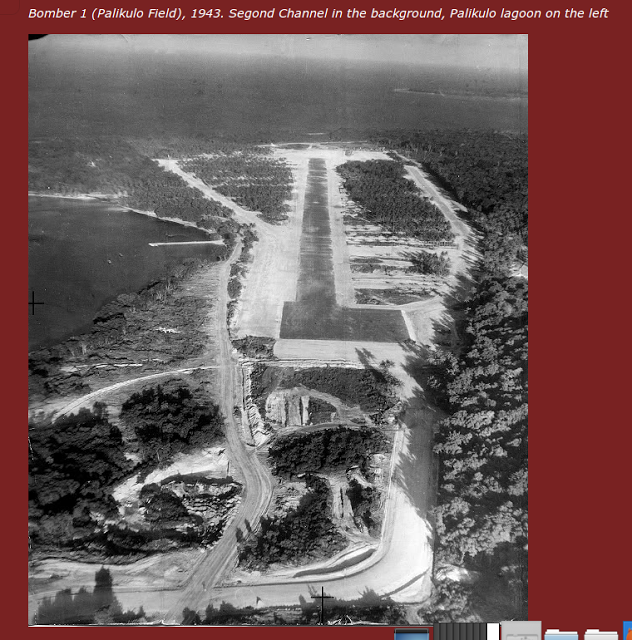

Suddenly huge ships landed carrying all kinds of strange equipment: trucks, bulldozers (to make roads for the trucks, there weren’t any yet) and about 40,000 people. I can imagine that few of the locals would have thought there could be so many people anywhere. And next thing they were building these:

That’s the first of at least four air fields they built. This one was usable in under two months. This was important because without an airfield they had to rely on boats and seaplanes for cargo and they needed lots of cargo fast. The first pilots to fly in did report the experience was more exciting than they hoped, but they did (mostly) manage to land safely.

They built a town on the coast just off the far end of this runway which had even had movie theatres as well as hospitals, workshops and so on. It seems impossible they could have moved so quickly on this, but they did.

While the scale of all this is fascinating I found myself wondering what the locals thought of it all. Fortunately they’re happy to talk about it.

This is Lino standing on one of the old runways. He’s a guide and if you go to Santos and want a look around he’s excellent.

It was not an invasion. The forward parties made an effort to talk to the locals, they told them that it was not safe on the coast because the Japanese would kill them, and that they should move inland. I’m not sure if that was true but the forward parties probably believed it. The important thing is that the process was friendly. They also needed labour and were happy to hire locals and pay them in, well, US dollars. What did they do with the money? Many of them buried it in a box somewhere and there are stories of old guys, feeling their end coming on, telling their family about some box of money buried in a forest. Subsistence farmers who own their own land have little use for cash and they had no banking mechanisms. Perhaps not so much on Santos but further south, on Tanna, they were so impressed by all this technology they made it into a kind of religion and so the cargo cults were formed. I’m not at all surprised. When you go from grass skirts to aircraft in a matter of weeks you’ll struggle to find ways to explain what is going on. Lino tells stories of ghost trucks making their way through the forest at night, though not now they’ve picked up much of the debris.

Relations seem to have stayed cordial between the military and the locals. It helped that a great many of the soldiers who arrived were black, just like the locals. Not actually the same race, but it meant people were less hung up about skin colour. At the end of the war everyone left. They bulldozed most of the buildings and then drove the bulldozers into the sea, which seems bizarre but there were reasons. During wartime everyone pulls together and those bulldozers (and trucks and everything else) were produced by US factories at cost. The manufacturers did not want them coming back to the US and being sold cheap, destroying their markets. They offered the gear for sale to Australia and New Zealand but not at an attractive enough price. With no supporting infrastructure they were no use to the locals, there was no source of fuel for a start, so they dumped them. However the stuff that was useful to the locals such as kitchen utensils and so on, they handed around.

It was mostly US forces, but not entirely. There were Australians and New Zealanders there, including my father who was at Palikulo Bay servicing electronics gear on the aircraft. He was always mad on electronics, built his own ham radio when he was 13, so this was an obvious path. He spent time on Guadalcanal and Santo, but he got there after the worst of the fighting was over. Nevertheless his diary records several air raids which probably were flying out of the Japanese base at Rabaul, close to PNG. Historical records of this time show there was little damage from these raids but they seem to have been fairly alarming. In the aerial photo of Palikulo Bay (above) Dad’s camp was near the base of the prominent jetty.

My father grew up in a small rural town and in his early childhood they had no electricity. The farm he lived on relied on horses rather than tractors. So, while it was not such a huge leap in technology for him to see this vast undertaking on Santo it must have impressed him more than I realised when he talked about it.

I found myself wondering if we can learn anything from this incidence of a low tech culture meeting a high tech culture for when, say, we eventually make contact with space aliens. We can expect the difference in technology to be very much greater. It seems unlikely that any space aliens we ever meet will be less than a million years or so ahead of our development and the difference here was probably a lot less than a thousand years. However this was also a case of the high technology running at full blast, so that accentuated the effect. If my father had turned up there with a horse and a plough it might have been a bit interesting to the locals, but not astonishing. An armada of ships deploying bulldozers, throwing up huge buildings and mowing down the forest would impress anyone even now.

Roger Parkinson

Roger Parkinson