I spent a pleasant afternoon hunting down some details about my long dead grandfather and the results are IMHO pretty interesting.

Anyone with any history has heard of the ‘Great Depression’ of the 1930s. Several countries associate it with a great leader who implemented Keynsean economic initiatives to rescue their hard pressed populations. In the USA it was Franklin D Roosevelt, in Britain it was Ramsey McDonald. In New Zealand it was Michael Joseph Savage. Working class homes here often had a photo of Savage on their wall and the man was looked on as an economic saviour. It helped that he was a quiet, modest sort of person and came to power around the time radio was widespread so his voice was heard in every home in the country on a regular basis.

But my research is not about Savage, it is about his Finance Minister Walter Nash. Nash obviously played a key role in any economic decisions and eventually became Prime Minister after Savage in 1957.

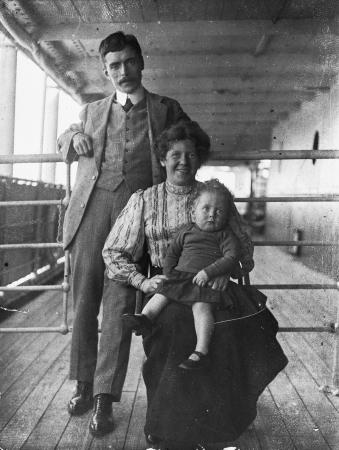

The family story I was following up on was that my grandfather, John Stych, was a friend of Nash. My mother told me this, and I think she said she recalled him coming to the house. She also said that her father had written to Nash when they were in dire financial straits during the depression and they all believed this letter was responsible for the introduction of a sickness benefit.

There were employment schemes at the time whereby the government made work for men (always men, actually) so that they could support their families. But my grandfather was too ill with tuberculosis to work. I gather the new benefit made all the difference.

Walter Nash and his wife Lottie.

I wondered if there was any truth at all to this story and I find there is, at least a little. There’s no evidence that my grandfather wrote to Nash, but he certainly knew him, and quite well.

Nash arrived in New Zealand in 1909 from Birmingham and he lived in Brooklyn, Wellington. He was a Sunday School teacher at St Matthew’s Anglican Church and he was a member of the Church of England Men’s Society (CEMS). He wore a CEMS medallion on his watch chain for much of his life.

He bought part shares in two tailoring shops, a business that eventually went bad and in 1913 he moved to Palmeston North and worked as a commercial traveller for a wool and cloth merchant.

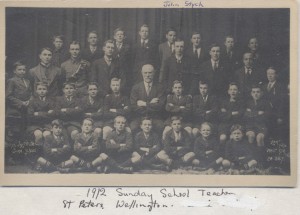

So we have Nash in Brooklyn between 1909 and 1913 and involved in the Anglican Church. John Stych also lived in Brooklyn and was also a keen Anglican. Initially the family attended St Peter’s because St Matthew’s was not formed until 1909, after that they are recorded helping out there at church fairs etc. John’s sister taught Sunday School at St Matthew’s but John himself taught at St Peter’s. That’s him in the third row from the front, 4th from the right. He was, however, very close to the Rev R H Hobday, vicar of St Matthew’s. Hobday got him into missionary work in Africa and he gave his address when he returned on furlough in 1916 as c/o Rev Hobday, Brooklyn because his family were dispersed by then.

Since these two, Stych and Nash, were so involved in the same church they would have certainly met. Not only that, John’s parents came from Birmingham, so there would be a connection on that level as well. John’s father died in 1904 but his mother was still living and also attending St Matthew’s.

John Styche’s CEMS medallionThen there is the CEMS connection. I have no family information suggesting John was a member of the CEMS but they typically wore a small Celtic cross on their watch chains, as did Nash. Photos of both John and his brother William show a similar cross on their watch chains. I even have John’s cross in my possession. I only recently learned it was his. I should add that the CEMS was also something Hobday was very interested in.

There was a CEMS meeting in 1915 at St Matthew’s with a lecture on “The Foundation and Principles of Socialism” by Mr H E Holland, presided over by Hobday. Holland was a key figure in the Labour movement, and the first leader when the Labour Party formed the following year. John was in Africa at this time and Nash would have been in Palmeston North by then. But this meeting throws light on the intellectual climate of the CEMS meetings at St Matthew’s under Hobday.

When he returned from Africa John worked as a ‘traveller’, which normally means commercial traveller, as did Nash and both were involved in the textile industry at some points. John was a draper’s assistant and we already noted Nash owned a tailor shop. The CEMS seems to have worked as an old boy network to some extent with members helping each other find employment, so it is quite possible John used that network to find work, and also possible Nash was part of that.

Finally in February 1921 Nash was convicted of importing seditious literature. John’s brother Thomas was similarly convicted in early April. The circumstances are different: Nash was working as a publisher’s agent in Wellington and said that the literature reached him as samples which he did not intent to circulate. Thomas claimed the literature had been thrown to him from a boat (he was found with the material on Hobson Street wharf in Auckland). Neither story sounded likely to the respective judges and the men were convicted and fined.

These two cases may be unconnected but the fact that they occurred so close together in time and that Thomas Stych and Nash may well have known each other too is interesting. The police at the time would, of course, have seen no connection. Thomas Stych was also convicted of refusing to serve in the army during WWI, something many of the founding core of the Labour Party shared.

This got me thinking about my grandfather’s time in WWI. He returned from Africa in 1916 and he offered himself for service and was pronounced unfit. We don’t have any information as to just why he was unfit. In Africa he had suffered from blackwater fever but he had several months to recover by then. The officer who signed this off was William Longhurst, his future brother-in-law. John subsequently went back to Africa to resume his missionary work. In practice he was seconded into helping administer the steamers on Lake Nyasa (now Lake Malawi) which were by then under the control of the British Military. I don’t know what his thoughts were about serving in the army, but he seems to have managed to avoid it one way or another.

Roger Parkinson

Roger Parkinson